Arte Povera: A Discourse on Postwar Italian Art by Leo Brisson

March 8, 2020

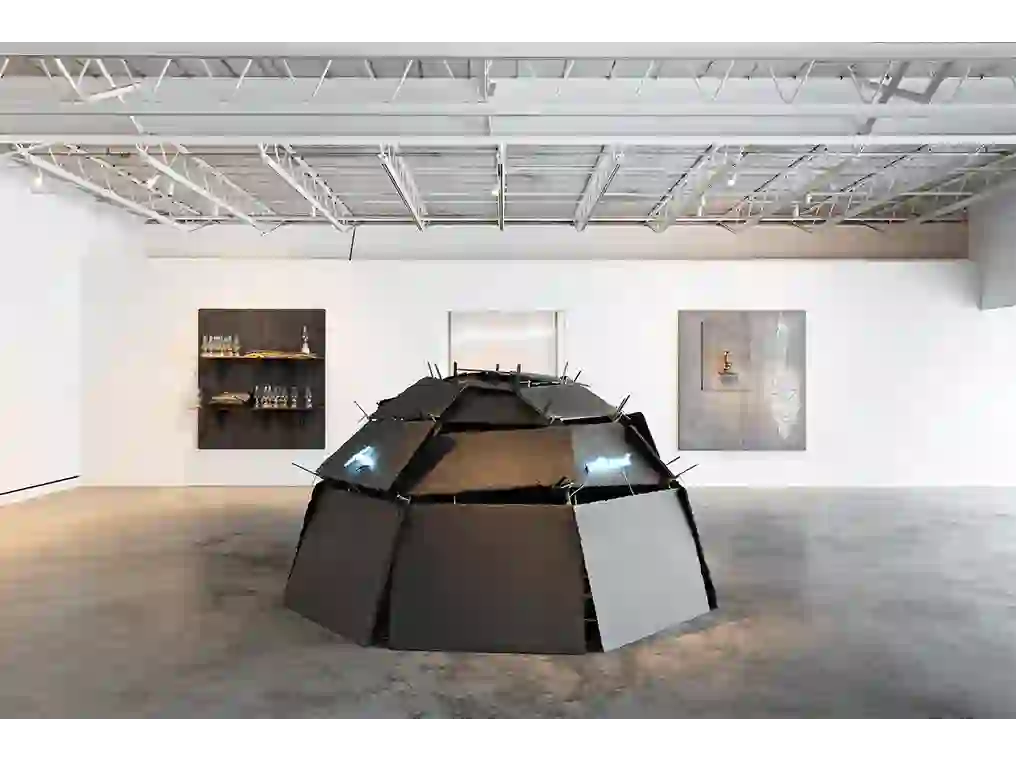

In April of 1968, artist Mario Merz debuted his sculpture Igloo di Giap in Rome. Translating to Giap’s Igloo, the structure was constructed with bags of clay suspended by a metal skeleton and featured bright, contrasting neon tubing over the igloo. The neon, spelling out Se il nemico si concentra perde terreno, se il disperde perde forza (“If the enemy masses, he loses ground, if he scatters, he loses strength.”) The statement reflected the strategies of Vo Nguyen Giap, a North Vietnamese war general. Elizabeth Mangini, author of “Solitary/Solidary: Mario Merz's Autonomous Artist,” writes, “The individual bags of clay combine to provide structure, shelter, and warmth for an individual inhabitant, yet when amassed for this purpose, they lose the potential for flexibility and mobility, and certainly the clay does not cover as much ground as if it were spread out on the earth.” (Mangini 16). Merz’s appropriation of guerilla war strategies, used in conflicts such as the Vietnam War, becomes a reference for then-relevant political, social and cultural events, such as Italian worker and student protests of the 1960s and 1970s. However, Merz’s work provided not an explicit discussion of guerilla war strategies, but rather a broad association of the concept of relationships between individuals and organization. Viewing Igloo di Giap in this way allows the work to transcend political statements and become a poetic work, specific to the viewer. Mario Merz’s work of 1968 continues to employ similar themes of political autonomy, guerilla war, and nomadism, all with a relatively limited use of material such as beeswax, neon, and metal. These early works exemplify the artistic efforts surrounding post-war Italian art. Much of the art of this age was defined by the work of several Italian artists and guided by a focus on both rustic and industrial materials to represent a range of political, artistic and cultural ideas. Within Italy of the 1960s and 1970s, global unrest as well as Italian post-war economic, cultural and artistic change led to a rise in the conceptual art movement known as Arte Povera.

The term Arte Povera represents not a specific thematic or aesthetic value; rather it refers to the work of several artists, mostly of Italian heritage and working generally in Northern Italy. However vague the term Arte Povera appears, translating to poor art in English, the phrase holds the unique ability to capture the guiding values of the movement. Poor in this sense demonstrates the unadorned value of art evoking a take it or leave it attitude, and leaving little space for art to exist in an aesthetically pleasing manner. With the inception of the movement in the late 1960s and with the aid of art critic Germano Celant, the movement was driven by political ideas, allowing for much of the work to be politically conscious, if not activist. The politics of the art world similarly played a large role, as did the styles of concurrent and previous art. Adopting commonalities between works, Arte Povera seeked to fulfill goals through key overarching principles. The movement was guided by the works of multiple founding individuals, and distinct works are made memorable by their impact on the movement and on the art world holistically.

Art of Resistance

To best understand Arte Povera, it is important to comprehend its status as a reactionary movement within post-war Italy. The movement was heavily influenced by political, social and cultural circumstances of the period, as seen in the work of those associated with the movement. Italy of the 1960s and 70s was dominated by American political and economic influence, through the preeminence of the Marshall Plan. This American involvement brought Italy to the status of an industrialized nation of economic prosperity. However, many Italians resented this involvement, rather looking towards political revolutions in South America and Asia as models for political and cultural change. The frustration with American involvement was furthered by resentment over American combat in Vietnam. Much of the artwork of post-war Italy reflected these political concerns in the creation of politically charged art. Arte Povera drew influence from domestic and global political and economic events and ideas of the 1960s and 1970s.

Following the loss of World War II, Italy suffered economically. With fear of a spread of Marxist ideas to a relatively impoverished Europe, the United States initiated the Marshall Plan, providing economic aid to many nations. The plan stimulated Italy’s economy and promoted industrialization. Nicholas Cullinan, author of “From Vietnam to Fiat-Nam: The Politics of Arte Povera”, a descriptive article introducing the political influences of Arte Povera describes this change, writing, “Together with American aid, the growth of companies such as the Turin-based automobile company Fiat (which by 1967 was selling more cars in Europe than any other company) and other firms such as Olivetti and Zanussi contributed to Italy’s burgeoning foreign trade. Yet this ‘miracle’ caused Italy a great deal of social tension and upheaval.” (Cullinan 13). Many Italians resented American interference, viewing the involvement in affairs as imperialist, rather focusing on Marxist concepts and looking to political revolution elsewhere for models of change. Individuals such as Mao Zedong, Che Guevara and Ho Chi Minh all provided hope for Italians, who resonated with a movement for political change and a shift of power through the practical application of Marxist principles. Furthermore, a common interest of many Italians included physically resistant guerilla strategies, as a means to resist American interference and fight for change.

Adopting the idea that a strong union representing the citizens of a given society would hold the potential to mobilize around a hope for change, guerilla strategies became an exciting opportunity for many Italians to effect change. As Cullinan explains, Italians turned to physical and violent revolution that evoked these ideas, writing, “As the revolution failed to materialize, optimism was replaced by impatience. What was now needed, they argued, was direct, violent action, which would destabilize the capitalist structure and make revolution inevitable.” (Cullinan 26). However, this feeling for a need of violence led quickly to terrorism, as fascist and Marxist groups both began to attack and kidnap members of the Italian government. A common wish to take down the government surrounded both ideologies, as William J. Stover and Jeffrey M. Capaccio, two authors explain. Stover and Capaccio describe this effort as, “[T]he desire to liquidate the forms of political democracy and provoke a civil war.” (Stover and Capaccio). The increase in violent actions led artists to stray from describing work as guerilla, as the idea of nomadism was then adopted as a means to reflect broad conceptual ideas.

As American aid following World War II stimulated Italy’s economy, modernization in infrastructure and technology allowed travel and movement to become easily available. The newly found ability was evident in Turin, where the car manufacturer Fiat invited Italians to explore mobility. Thus, the concept of nomadism is symbolic of a consumerist culture and its pervasion of a previously agrarian Italian society. However, the newly found value of nomadism became another way to protest a way of life labeled as capitalist. Rather than a static life burdened by routine and participation in the purchase of goods, counter-culture communities established communes and looked to traditionally nomadic cultures as inspiration for a life free of burden. In Arte Povera, nomadic imagery such as the tent or igloo is appropriated in order to recognize the fluidity and mobility that many Italians strove to achieve. In addition, the temporary structure serves to protect a dweller from the figurative dangers of the world.

However, along with a wish to free oneself from a cumbersome environment, one must participate in a consumerist society, effectively providing a paradox. In her essay, “The Discourse of Modern Nomadism: The Tent in Italian Art and Architecture of the 1960s and 1970s,” writer Silvia Bottinelli describes the ideas of one Arte Povera artist, Gillberto Zorio, writing, “In Zorio’s work, the image of the tent elicits complex references. Nomadic dwellings represent alternative ways of living; alternative lifestyles, however, still rely heavily on knowledge acquired in the context of industrial societies and on the use of commercially available materials.” (Botinelli 71). This duality represents the recurring idea in which a person becomes trapped between freedom and burdensome existence, a space occupied by many artists of this post-war movement.

The complex paradoxes and broad conceptual themes explored extensively in Arte Povera recognize a unique ability to draw on societal circumstances to create works that not only represent these ideas, but become statements of their own. In this way, works of the movement can be viewed as revolutionary even long after the end of the movement in the 1970s. However, understanding the political sphere surrounding the artists of the time ensure for a full comprehension of the works themselves. Furthermore, an understanding of the artistic circumstances of the time further demonstrates the goals and influences of artwork.

Contextualizing Arte Povera Within the Artistic World

Accompanying the politically charged movement of Arte Povera, artistic influences fueled the work of artists associated with the period. However, the movement’s passionate anti-Americanism was reflected in a widely-shared hatred of the majority of contemporary American art. Furthermore, the presence of a variety of media in the movement was associated with the influence of several styles and movements. Older European styles such as Baroque were looked upon as impressive and important in the distinctly Italian movement, while American Pop Art was fully rejected in association with American political involvement. In contrast, performance art-based works were introduced into the movement, and suggested the influence of modernist efforts such as Dada and concurrent avant-garde movements like Fluxus.

Artists of the movement felt a strong connection to Mediterranean culture, as expressed in the widely-held appreciation of Baroque artwork. Giuseppe Penone, an artist associated with the inception of Arte Povera, highlights his personal appreciation for Baroque-era works guided by material in his interview with Martin Gayford, an art writer. Gayford explains, “This sense of the physical qualities of the stone, wood and the other substance he transforms into art links Penone to his Italian Predecessors. ‘Bernini,’ he points out, ‘had a great feeling for the nature of the material, and he used them in a very sensual way’.” (Gayford 2). Following the Baroque-era idea in which importance is placed on the material, artists like Penone apply modernist conceptual themes to art objects, which honor the material involved. This idea is present in Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Venere degli stracci, in which Pistoletto most literally brings the style of Arte Povera’s common objects in unity with a Baroque sculpture. However, most often the themes carried from the Baroque era are depicted subtly in the thoughtful choice and reflection upon the art object.

At times, however, Arte Povera introduces uniquely modernist themes and practices, such as performance and installation art emerging from the Dada movement of the early 20th century. The radical experimentation in how art is presented and contextualized highlighted is a major theme in Dada, as artists worked in diverse media in order to liberate art and the artist from the constraints of an encumbered world in the midst of a tumultuous environment shaken by the Great War. The experimental work of Dada led to Neo-dada movements like Fluxus working similarly in order to question preconceived notions of art, this time in media reflecting emerging technology of the 1960s. Fluxus also placed importance on performance as a means to dematerialize art in a consumer world. The concept of disencumbered artworks runs parallel to the tendencies of Arte Povera artists to use performance art, installation art, and work outside of traditional means. However, Arte Povera not only represented a cumulation of previous and concurrent movement, as the members of Arte Povera expressed frustration with American popular art. As American Pop Art grew, Italian Arte Povera artists rejected the style, drawing on a frustration with American involvement with Italian affairs. This socio-political reaction became tied to the anger felt by Italian post-war artists as Pop Art entered Italian galleries. Nicholas Cullinan exemplifies these feelings in his citations of Italian art publications in which authors mock and insult Pop Art as a weak movement acting far from the America known for innovation in other fields. Many members of the art community in Italy at this time viewed the imagery of Pop Art as an extension of American consumerism that they felt had pervaded Italian life. The hatred for American mainstream art manifested itself within the Arte Povera community with protest of Pop Art; however artwork tended to concern American political affairs rather than the conflict existing within the art world.

Artistic influences represented a defining factor in Arte Povera as a movement conceived from a wish to invoke an artistic revolution of sorts in the transformation of art into a conscious body of works. And central to the progression of Arte Povera existed the interdependence within the community. As a movement central to the metropolitan area of Turin in Northern Italy, artists used the work of those around them in order to generate distinct styles. As a result of influence within the movement, Arte Povera was able to reach a unique and recognizable style, even though the movement acts as a general group of artists rather than a concrete stylistic idea. These commonalities are manifested in conceptual principles shared by many artists.

Defining principles of Arte Povera

Surrounding Arte Povera were a number of common artistic concepts that helped to create a sense of unity between the work of those associated with the movement. Artists important to Arte Povera commonly maintained a strong value that an idea governing a work became more prominent than the art object in the foundation of conceptual art. Therefore, much of Arte Povera artwork possesses a sense of meaning and message, however broad this concept may be. As expressed previously, greater political, economic, social and cultural events and ideas were expressed through artistic principles both at a specific craft-related level as well as a conceptual level. Central to the movement was a sense of dematerialization and dismemberment of the art object, which was expressed physically in the overwhelming use of inexpensive material and use of nature as a means to respond to growing frustration with artistic, political and economic events. Furthermore, artists of this time continuously made efforts to expand artistic ideas and experiment with new ideas.

As Arte Povera developed its principles as a modernist movement, many artists began to create works that removed layers of artistic complexity. These encumbrances existed both concurrently and previously in the history of art and made for symbolically rich pieces in which visual and conceptual complexities defined the work. Artists such as Alighiero Boetti and Michelangelo Pistoletto set out to challenge this value with seemingly simple works. Pistoletto’s Oggetti in meno illustrates the concept of a disencumbered art object with a series of works that lacked a commonality as seen usually in an artistic display. Pistoletto describes his goal, writing, “Each successive work or action is the product of a contingent and isolated intellectual or perceptual stimulus that belongs to one moment only. After every action, I step to one side, and proceed in a different direction from the direction formulated by my object, since I refuse to accept it as an answer.” (Pistoletto, A Minus Artist, p. 19). In removing consistent ideas from his collection of works, Pistoletto removes a sense of expectation from the viewer. Among Pistoletto’s Oggetti in meno, stand a wooden frame which becomes two wooden seats and a table. The display, a seemingly constraining setting, acts as a social cue to possibly sit with a friend. Another work, titled Casa a misura d’uomo (“House on a human scale”), adopts the idea of a child’s playhouse at the scale of an adult. However, the work is on a scale much too small for any adult to comfortably occupy. Pistoletto’s Oggetti in Meno explore little other than visual ideas, effectively placing the work away from conceptual artwork. Alighiero Boetti disencumbers the ordinary and mundane and frees them in such a way that a new art object is created, without the preconceptions of a purposeful utility while creating a piece that serves little purpose other than to jar the viewer out of the expected possibility and creates a sense of quizzical reflection, establishing the potential for a new reality. This is represented in Boetti’s Sedia e Scala (“Chair and Ladder”), in which the prefabricated utility is reformed into a purely geometric object. The work seems familiar to the viewer, prompting the false security of a known purpose, which is then quickly preempted by the realisation that the new forms are rendered seemingly useless, other than for an artistic statement. Boetti disencumbers the chair and ladder by breathing new life into an object that was burdened by its previous purpose.

Arte Povera drew largely from the concept of nomadism, in the creation of works exploring nomadism as an anthropological concept as well as a means to examine broader and less specific feelings such as movement, mobility and flexibility. As a result of Italy’s economic success of the 1950s and 1960s, Italians explored ideas of mobility in an industrialized world. As a modernist movement, many artists employed the idea in the quest to develop Arte Povera works. Artists like Mario Merz employed the tent in order to represent a relationship governing the individual and the group. Merz’s common use of the igloo appropriated the nomadic object as a means to symbolize guerilla strategies in both war as well as efforts for social change. As a temporary settlement, the tent or similar nomadic object becomes a symbol for a fleeting, mobile life. Furthermore, Arte Povera develops a relationship between nature, as a setting and the settlement, as a man-made product of culture. This relationship tends to sit at the core of Arte Povera, governing works in which physical products of nature are blended with industrial goods. However seemingly opposite and contrasting these two elements seem, Silvia Bottinelli cites Claude Lévi-Strauss to state that these two ideas become undoubtedly unified by common cultural meaning. Lévi-Strauss explains, “[C]ultural products are no longer intrinsically different from natural ones, language obeys the same laws that regulate cells” (Lévi-Strauss). Lévi-Strauss goes on to explain that Arte Povera becomes a means to govern nature and cultural objects under a common artistic goal, effectively relating the two elements.

Guiding Figures of Arte Povera

As a relatively limited movement, constrained regionally and within the span of less than a decade, Arte Povera was guided by the work of a small number of artists. The group was united by a mainly Italian origin, and was made up mostly of men who were brought together by a memory of Italian facism and World War II. This recollection of a destructive facism and the struggle of World War II provided for a unique perspective shared by many artists and allowed Arte Povera to exist as an undoubtedly Italian art form. Between the many transformative artists of the movement, several individuals reflect the core concepts of Arte Povera through works that originally defined the art movement and allowed for the expansion of artistic ideas through experimentation. Mario Merz, Alighiero Boetti and Michelangelo Pistoletto all developed unique styles during this period that allow for an understanding of the movement when studied critically.

The work of Mario Merz reflects a form of Arte Povera that prioritizes activism most importantly through pieces of politically conscious artworks. Mario Merz was likely the most politically involved of Arte Povera artists, identifying closely with Marxist ideas such as Organized Autonomy, a political concept that wished to remove seemingly oppressive structures through individuality. Autonomy centered around a wish to rid society of hierarchy by removing political structures. However, the idea of autonomy not only existed with strict political terms, as it was appropriated to signify strict individuality and liberty much like nomadism. Merz reflected both ideas of autonomy and nomadism in his April, 1968 artworks. Merz made use of the igloo to symbolize nomadic ideas while linguistic references identified more activist priorities like the Vietnam war. However, works like Igloo di Giap not only reflected political and cultural meanings, but were left to a degree open-ended, allowing alternate interpretations to arise within the viewer of the work. Furthermore, Merz’s simplistic use of material to build ideas was further represented in his common use of beeswax and neon held by metal. Merz’s 1968 work, entitled Solitario, Solidale (Solitary, Solidary), portrays the two words in neon, both sitting on a bed of beeswax. The slight heat from the neon slowly melts the beeswax as the words sink into the material. The work reference parisian graffiti, which in turn, references the short story, “The Artist at Work,” written by Albert Camus in 1957. The short story examines the relationship existing between the solitary work of an artist and the solidarity existing in the art market that an artist must participate in. Merz’s use of this juxtaposition illustrates the position in which an artist must exist. The work not only demonstrates Merz’s ability to demonstrate political and poetic work, but also exemplifies his thoughtful and purposeful use of material. Merz chooses beeswax to subtly signify the collective work of the bees, which work together in a common goal. Similarly, neon, appearing as one material, actually consists of many individual particles.

Merz’s meaningful choices of common materials as a vehicle for his conceptual themes became a defining aspect of Arte Povera and exists amongst the work of all artists associated with the movement. In addition, much of Merz’s work helped to catalyze early thinking about Arte Povera as Merz debuted series in the spring and summer of 1968. Mario Merz’s works can be seen as relatively conceptually dense with political and poetic connotations guiding this work.

However, Alighiero Boetti, a peer artist, favored rather disencumbered art objects in his quest to develop a reactionary movement. Early in his career Alighiero Boetti rejected the label of artist. Similarly, Boetti’s work seems to both skirt the line of Arte Povera and fully embrace the movement through works predating the period and exploring use of separate materials. Boetti was among a group of artists to touch on ideas that seemingly evoked memories of Dada in that the oeuvres questioned the meaning and status of art. Boetti accomplished this through continuously disencumbering both the art object and the role of the artist. This strategy is seen clearly in Boetti’s exhibition at Galleria Christian Stein in 1967, in which Boetti brought almost thirty seperate pieces, all art objects into the gallery without a formal theme governing all of the works. Boetti’s signature take it or leave it attitude of the time is present with his rejection of traditional means of exhibition. Art writer Tommaso Trini describes Boetti’s exhibition, writing, “the show consists of finite propositions in their plurality and divergence. The work obliges us to decenter our reactions from one work to the next. The operation consists of horizontal elaboration” (Tommaso Trini, “Boetti o la costruzione non ricostruita,” Domus, no. 457 (January 1967). pp. 29-30).

Trini’s discussion of horizontal elaboration refers here to Boetti’s anti-hierarchical stance in portraying a large variety of mediums together. Boetti seeks to remove an expectation for the artist to work in a single medium and represent a single idea. Furthermore, the art can be easily related to guerilla strategies and autonomy as the individual piece is considered as a stand-alone concept while making up a greater series of works, which all collectively question the expected. As a series originally debuted in 1967, Boetti’s exhibition can be seen as a influence on later Arte Povera principles. In addition to Boetti, the work of other Arte Povera artists seek to forward the period with the development of unique themes.

Among the group of artists that made up Arte Povera, Jannis Kounellis, a Greek-born artist, represents a slightly separate heritage; however, he was welcomed within the community of Italians. Kounellis’s art was courageously unique in his bold inclusion of live animals in order to reference the art of the past. In 1969, at Kounellis’ exhibition at Galleria L'Attico in Rome, the artist tethered 12 horses to the gallery walls in a study reminiscent of the horse in the discourse of Western art. The horses in this way effectively recall architecture in which sculptures of horses were used to line buildings. Kounellis himself discusses his work in an interview with Martin Gayford. Kounellis recalls, “‘It isn't a Pop Art image. It was calculated and came out of living in this city that has an incredible history underneath it. It was modern but not modernist, and modern despite being ancient'.” (Gayford). Kounellis here describes his wish to create new, unique art through the acknowledgement of past art and history. Within the artistic community that Kounellis began to identify with, Michelangelo Pistoletto, a founding member of Arte Povera, acted somewhat as a leader to his contemporaries. Pistoletto’s work embraced figurative aspects of older Italian art while juxtaposing the figure with aspects of modernism. Pistoletto’s Venere degli stracci (Venus of the Rags) shows a nude sculpture immersed in colored rags.

Portraying both the romantic realist sculpture and the seemingly abstract pile of cloth brings into question the existing expectation that modernism would separate from Baroque, Renaissance and other older European art periods. This notable work demonstrates the importance that Pistoletto demonstrated on a movement associated largely with modernism. The influence that he had is evident in the work of other Arte Povera artists.

Although Arte Povera orbited around a focused group of artists, understanding the movement holistically requires a reflection on other specific works. However confined Arte Povera was to a union of artists, the movement’s range of conceptual themes and aesthetic ideas pushed past personal ideas. As a then promising movement, Arte Povera was relatable for not only Italians, but for others who identified with the many times open-ended pieces. In fact, identifying pieces of artwork that defined the period is an important step in gaining a broad comprehension of the important values governing the movement.

Notable works of Arte Povera

Central to Arte Povera, key works stood as important reflections on overlying themes, as previously discussed in the present paper. As genre-defying artists gained notoriety with the development of common strategies, other pieces demonstrated the way in which an Arte Povera artist approaches a concept and develops an art object. While artists demonstrated contrast in the specific choice of material and themes, Arte Povera gained much of its status as a unique movement through a focus on material as a means to examine an idea or a set of concepts. This commonality is displayed in no better way than the distinct works entitled camping by Emilio Prini, Zorio’s Tent by Gillberto Zorio and Pistoletto’s Minus Objects.

Emilio Prini’s camping unites the common theme of nomadism with the aesthetically charged and visual aspect of performance art. Pitching tents across from the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1969, the artist prioritizes the process in creating the art, with the methodical construction of the nomadic object. Bottinelli writes, “The artist’s focus was on the performative connotation of the work. A list of complex actions, delineating a circular space, choosing points within that circle, and pitching tents at each point.” (Bottinelli 71). The planned action reflects the curated aspect of Arte Povera as the piece itself explores a physical model of nomadism as understood naturally. The theme of nomadism is represented differently in Gillberto Zorio’s 1967 piece, Zorio’s Tent, in which a tent is constructed out of pipes and fabric while saltwater poured onto the top of the tent creates a small basin and drips onto the ground. Zorio chooses to study the aesthetic themes of movement and fluidity, exemplified by the water and confirmed by the use of pipes, symbolizing a passage for energy. The piece illustrates the drawn out process governing movement and provides a physical representation which seemingly evokes the assemblage-based aspect of interaction without inviting the viewer to pour salt water. The piece evokes a distinctive simplicity in the form of a single object. Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Oggetti in Meno seeks to adopt the attention of the viewer while serving as an object removed of the burdens existing in the piece. Pistoletto’s series of objects seemingly invite the viewer into the piece, challenging a history of art that has encouraged a strictly distant relationship between viewer and art. Karen Pinkus describes this, writing, “What makes Pistoletto’s objects ‘minus’ or ‘less’ has little to do with materiality and more to do with the artist’s concept of them as liberating him and his body from traditional constraints. In arte povera, then, the body of the artist enters into the work, at times making institutionalization highly problematic.” (Pinkus 65). Pinkus identifies Pistoletto’s attempt to disencumber all relationships in art, as the work seems to encourage a physical body to, for example, enter a chair or relate the size of a miniature home to the stature of a person. Pistoletto here subtly highlights a powerful and key idea within Arte Povera, in which frustration with the existing artistic status quo restricts experimentation.

The works of Arte Povera, as both conceptual and to a degree ‘anti-art’ gain a sense of importance when critically examined. However, at times the commonly paradoxical themes of capitalism, autonomy and the individual can seem overwhelming when identified in works, as the continuation of an ever present art market limits the movement as efforts to make cultural and political change through art never succeed in their original goal. However this common effort to transform public belief in art and society feature a variety of means and mediums.

Works such as Zorio’s Tent, Oggetti in Meno and camping demonstrate contrasts between performance art and assemblage. The variety of mediums, importance placed onto the art object, and conceptual principles of the Arte Povera world allow for further art movements to develop aesthetic and conceptual ideas directly and indirectly inspired by the post-war movement.Arte Povera, as a modernist art form placing importance on material, inspired the work of concurrent and later art movements which understood the bold artwork surrounding activist efforts and examinations on the human condition. Generally, Arte Povera can be credited with a progression of modernism into a more partisan role, as the movement applied activist ideas to artwork while expressing universal themes, as described in the essay, “Parallel Revolution: Elizabeth Mangini on Arte Povera.” Mangini writes, “Arte povera’s model of tactical engagement is instructive today, since it protects artistic freedom and eschews partisanship. In short, such works focus on the macrocosm of human experience, not the microcosm of single-issue politics.” (“Parallel revolution”). This impact is identified in the work of Nairy Baghramian, a German artist, whose post-modernist sculpture parallels the conceptual themes of political and societal commentary through the disencumbered art object. Her art serves as a reaction to a consumerist and capitalist artistic culture, as Andre Rottmann describes in his overview of Baghramian’s work. Rottmann writes, “Bagrhamian employs various counterstrategies in order to reflect on the conditions of current artistic practice and the possibilities of sculpture in particular within our global political economy of commodities, services, and goods.” (Rottmann 290). Bahrhamian demonstrates her counter strategies in public art, as seen in her work Aufbauhelfer, a 2009 exhibit, in which two structures present in two locations both were dysfunctional as both art and usable items. Arte Povera’s distinct impact on sculpture from its emergence in the late 20th century onwards is similarly existent in the artwork of Mono-ha, a Japanese avant-garde movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The movement parallels a focus on industrial and natural materials seen in Arte Povera. Midori Matusi explains that Kishio Suga, “presented sculpture as a unique object or ‘thing’ that alters spectators’ perceptions rather than as a aesthetic object.” (Matusi 1). Suga’s wish to challenge the role of the viewer reflects the same principle embraced by creators of the Arte Povera sphere. Evidently, the far-reaching impact of Arte Povera holds the power not only to inspire the artist, as the effort to radically change the public opinion on art and the art market holds an undeniable value in the movement. Arte Povera sets out to transform the way in which art is viewed, understood, distributed and shown and encourages the spectator to understand and achieve this change as well.

Bennett, Christopher G. “Substantive Thoughts? The Early Work of Alighiero Boetti.” October, vol. 124, 2008, pp. 75–97. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40368501. Accessed 11 Feb. 2020.

Bottinelli, Silvia. “The Discourse of Modern Nomadism: The Tent in Italian Art and Architecture of the 1960s and 1970s.” Art Journal, vol. 74, no. 2, 2015, pp. 62–80., www.jstor.org/stable/43967619. Accessed 11 Feb. 2020.

Cullinan, Nicholas. “From Vietnam to Fiat-Nam: The Politics of Arte Povera.” October, vol. 124, 2008, pp. 8–30. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40368498. Accessed 6 Feb. 2020.

Gayford, Martin. “Root and branch: Martin Gayford talks to the men behind Arte Povera, who took modern art back to the natural world and the past.” Spectator, 24 Sept. 2016, p. 44+. Gale Academic OneFile, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A464883678/AONE?u=nysl_sc_ithhsl&sid=AONE... 44678e61. Accessed 9 Feb. 2020.

Mangini, Elizabeth. “Solitary/Solidary: Mario Merz’s Autonomous Artist.” Art Journal, vol. 75, no. 3, 2016, pp. 11–31., www.jstor.org/stable/43967690. Accessed 11 Feb. 2020.

Pinkus, Karen. “Dematerialization: From Arte Povera to Cybermoney through Italian Thought.”

Diacritics, vol. 39, no. 3, 2009, pp. 63–75. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23252697. Accessed 8 Feb. 2020.

Potts, Alex. “Disencumbered Objects.” October, vol. 124, 2008, pp. 169–189. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40368506. Accessed 5 Feb. 2020.

Whitfield, Sarah. “Arte Povera. London and Minneapolis.” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 143, no. 1183, 2001, pp. 645–646. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/889304. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020.

Stover, William J., and Jeffrey M. Capaccio. “SOURCES OF ITALIAN TERRORISM.” Peace Research, vol. 14, no. 1, 1982, pp. 11–19. JSTOR www.jstor.org/stable/23610138. Accessed 5 Mar. 2020.

Gayford, Martin. “Drawing from life.” Apollo, vol. 183, no. 641, Apr. 2016, p. 44+. Gale OneFile: Fine Arts, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A451633655/PPFA?u=nysl_sc_ithhsl&sid=PPFA... 9638d9. Accessed 5 Mar. 2020.

Mangini, Elizabeth. "Parallel revolution: Elizabeth Mangini on Arte Povera." Artforum International, vol. 46, no. 3, Nov. 2007, p. 159+. Gale OneFile: Fine Arts, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A171325985/PPFA?u=nysl_sc_ithhsl&sid=PPFA... d5ef46. Accessed 7 Mar. 2020.

Matsui, Midori. “Kishio Suga: Tomio Koyama.” Artforum International, vol. 46, no. 9, May 2008, p. 400. Gale OneFile: Fine Arts, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A179269268/PPFA?u=nysl_sc_ithhsl&sid=PPFA... bcf047. Accessed 7 Mar. 2020.

Rottmann, Andre. “Trace elements: Andre Rottmann on the art of Nairy Baghramian.” Artforum International, vol. 50, no. 10, Summer 2012, p. 288+. Gale OneFile: Fine Arts, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A294299325/PPFA?u=nysl_sc_ithhsl&sid=PPFA... 6821e4. Accessed 7 Mar. 2020.